EduSkills Blog: Apprenticeships – Helping Young People at Risk?

Apprenticeships – Helping Young People at Risk?

Maja Gustafsson | Researcher Education and Skills

A new OECD report looks at how apprenticeships across some of the OECD countries are tailored to young people who are unemployed and not in education or training, or as OECD calls them: “at risk”. Often, these young people share some common disadvantages such as weaker literacy and numeracy as well as ‘soft’ skills, which create barriers to taking up education or employment.

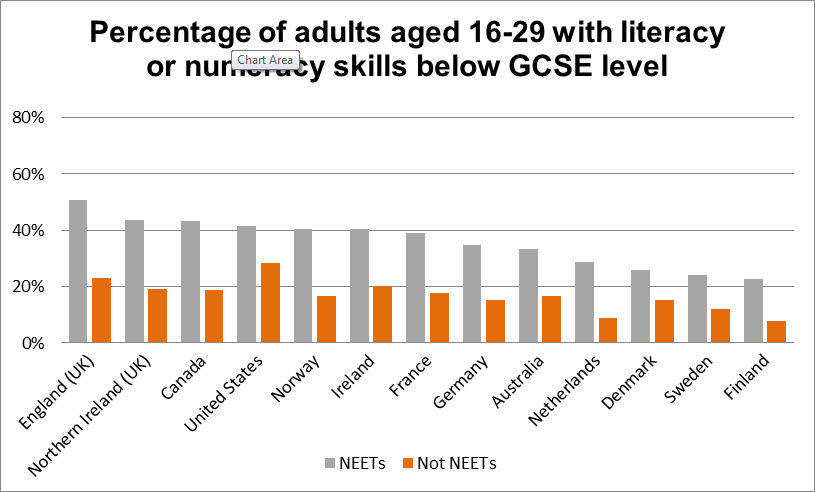

Comparing the literacy skills of young population at risk in England to similar countries is an alarming undertaking; over half of young people who have weak literacy or numeracy skills in England are out of employment, education and training. This is a significantly higher proportion than what we see in competitor countries such as United States (41%), Germany (34%) and Denmark (26%).

How can apprenticeships better help young people at risk?

Undeniably, the viability of apprenticeships rely on employers being willing to take on apprentices. If successful, this set-up allows the education and skills sector to remain fluid enough to adapt to rapidly changing economic conditions. For individual learners, however, this also means that their apprenticeship must align with business interests and bring value to the organisation.

Apprenticeships in England have been seen as both vehicles for enabling social mobility and improving skills to adapt with a rapidly changing world. This was reflected in the discussion at our most recent roundtable with the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Skills and Education, where delegates emphasised the possibility of apprenticeships acting like a social ladder, particularly if their reputation and prestige were improved.

Yet evidence from Germany, Switzerland and England, for instance from the Young Foundation, suggests that young people at risk may find it particularly challenging to complete an apprenticeship. According to the OECD report, apprentices with a minority background, weak school results and learning difficulties in these countries experience higher drop-out rates than their more privileged peers.

Supporting young people at risk during apprenticeships

The OECD report highlights the need for tailored support for young people at risk to help make apprenticeships worthwhile both for the individual learner and the business taking them on. This support is not to be limited to the application process, where schools and careers advice already have been emphasised as key factors, but extend throughout the duration of the programme.

For instance, a successful programme in Switzerland tailored to disadvantaged young people focuses support on the first two years of an apprenticeship. In contrast to the standard apprenticeship programme of three to four years, this scheme, co-delivered by schools and firms targets young people over 15 who are at risk of dropping out education and training or are struggling to find a full three or four-year apprenticeship.

The programme is similar to the typical, full apprenticeship, but students receive more support measures, such as individual tutoring, in-company supervision and remedial courses. In contrast to traineeships in England, when students finish, they can either find employment immediately or progress to the second year of the standard three or four-year apprenticeship programme. With student progression signalling individual success, participating firms also break even financially.

Austria provides another example of good practice. Support from third party mentors help to overcome some of the challenges that apprentices face during their program. Teaching assistants work extensively with apprentices designed for youth at risk and youth with special needs.

The teaching assistants are funded by public resources and take care of administrative preparation for the apprentice, provide tutorial support and act as mediators in case of difficulties and disagreements. For instance, they can provide invaluable support by assisting with everyday problems, preparing for assessments and act as mediators between the apprentice and their school or firm.

The teaching assistants often have previous experience working with disadvantaged young people and are trained in special education. Similar support services are available in Germany, where evidence suggests that more tailored support play a crucial role in apprenticeship completion rates.

For the future

There is a need for a more formalised support structure for young people at risk undertaking apprenticeships. In the highly marketised and fragmented system of technical education in England, it may be difficult for apprentices, schools, their parents and their employers to know where to turn if they experience problems.

A clear and reliable support network, whether as a third party or hosted in colleges or firms, that can support and mediate conflict between apprentices, schools and employers could increase confidence in apprenticeship paths and strengthen their role as improving social mobility by helping everyone complete the schemes they start.